David Ruggles/Hannah Randall House, Florence, Massachusetts, Part Two

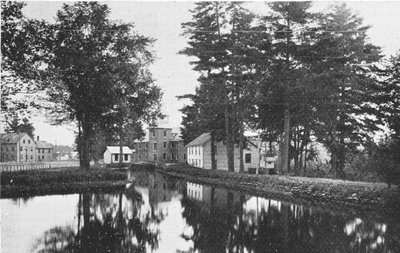

Northampton Association Factory Boarding house (center). Both David Ruggles and Sojourner Truth lived here along with nearly eighty other members of the Community. Ruggles moved into the Dr. Barrett oil mill house late in 1845.

Northampton Association Factory Boarding house (center). Both David Ruggles and Sojourner Truth lived here along with nearly eighty other members of the Community. Ruggles moved into the Dr. Barrett oil mill house late in 1845.David Ruggles continued his treatment for eighteen months and arrived at a point where his eyesight and his general health improved. He was left with a general sensitivity of touch that he felt allowed him to sense the state of health of others. With the primitive equipment he had purchased for his own cure he slowly began to help his fellow Community members. By June of 1844 the Northampton Democrat reported his first “cure.” (The North Star, March 17, 1848)

Dolly Stetson and her sixteen year-old daughter Almira refer to David Ruggles in familiar and affectionate tones in their letters to James. It is possible they had followed his career in New York with regional pride since he was from Norwich, CT. only 25 miles from Brooklyn. They likely read the Liberator and other abolitionist journals where he published numerous articles. Occasionally Ruggles himself would communicate his needs to James as when he asked “His Esteemed friend Stetson,” on June 20, 1844 to find him “an India-rubber syringe…indispensible to my progress in the “Water Cure.” He chastises Stetson, through his wife, for not supplying copies of Frederick Douglass’s newly published Narrative for which Ruggles appears—remember his bookselling background—to be a kind of local agent. (DWS to JAS, June 19, 1845).

After April of 1845, the Stetsons’ letters interspersed matter-of-fact details of life in the boardinghouse with descriptions of torturous meetings where the fate of a Community faced with mounting debt was being argued. Finally, the decision to sell off the silk factory boarding house and 100 acres to George W. Benson and a group of local investors would dislocate the Stetsons, Ruggles, and scores of other NAEI members and their families. In the mean time, David Mack, now thoroughly exhausted by the internecine strife, his health failing, his wife Maria’s precipitously so, elected to leave the Association and seek hydropathic treatment from Robert Wesselhoeft who had established himself in Brattlboro, VT. His departure would spell the end of the Association’s school (DWS to JAS, May 22, 1845).

At this point, David Ruggles appears to have begun arranging for his move to the Mack house—the former Benjamin Barrett “oil mill house.” Dolly writes to James that Ruggles needed blinds for six windows to be prepared in Boston and sent via William Parker (DWS to JAS, May 29, 1845).

…he wishes you to procure for him 6 window curtains or blinds of the following dimensions 4 ft 4.5 in long by 2 ft 6 in wide provided they can be obtained for 2 dollars or less. They may be sent by Mr. Parker on saturday.

I suppose you understand what they are. They are made of small splits of wood woven like the rush curtains—Mr Ruggles says they are sometimes sold for a shilling apiece…Mr Ruggles says you can find the blinds at the wooden ware stores or furnishing stores.

Harriet Hayden and Sydney Southworth: Married Out of Wedlock

Before David Ruggles could make the move, however, one other Community drama was to be played out at Mack’s house. Harriet Hayden and Sydney Southworth had, without benefit of clergy, married one another on an evening in July of 1844 (DWS to JAS, July 26, 1844). For this they were in effect shunned by the majority of the members. The Association had taken pains to abide by conventions relating to marriage if not just to rob their critics of at least this possible accusation of impropriety. David Ruggles himself had advised them to leave (DWS to JAS, July 26, 1844).

David Ruggles told them the other day that he knew from the opinions he had heard expressed by a great many that they never would be admitted here as members and they had better go while the weather was warm than to wait until fall when Sydney’s year was up. That set them in motion again to go but about this time Harriet was taken raising blood from her lungs and has raised more or less every day since…

In his commentary to the Stetsons’ letters, “Coloring Utopia,” Paul Gaffney points out, “That a black man would have a talk with a young white couple…certainly violated the social code on color and sexuality. Yet Dolly Stetson reported it to her husband rather plainly. It fitted her sense of Ruggles as close to the leadership and as a member of the community with a decided moral authority.” (Letters from an American Utopia, page 260).

Harriet and Sydney did leave, temporarily, to try another community in Ohio, but returned a year later to be near their friends. Harriet’s life was near over—the final stages of tuberculosis had set in. She had written ahead to ask permission to return to die at the place of her “early love.” (Northampton Free Press, May 16, 1862) At the same time decisions needed to be made about where the inhabitants of the factory boarding house would reside.

What ever we do we must do or decide to do soon—it is said that the factory must be emptied by the first Sept—Mr Macks family leave in July. We are to have no more schools after June—Sophia Foord, Elisa Wall, probably John Prouty and I know not but all in the house leave with Mr. Mack or before Sydney and Harriet have returned right glad I think to find a shelter for their heads. Harriet is very low in consumption and Sydney has had the chills and fever hold of him and looks miserably. They are at Mr Macks… (DWS to JAS, May 22, 1845)

A month later Harriet was dead.

[She was] buried the night before last by moonlight. I did not go to the funeral myself but those that were there said the services at the house were very appropriate and the burial very solemn and impressive. They had singing [and] reading from the New Testament and talking by several—Sydney is very much out of health and looks as if he would follow her to the spirit land soon. (DWS to JAS, June 19, 1845)

David Ruggles’ Northampton Water Cure

On January 1, 1846, eleven months before the formal dissolution of the NAEI, David Ruggles entered into an agreement, amounting to a lease with an option to buy, for Benjamin Barrett’s “oil mill house (so called).” (Hampshire County Record Book 111, page 6.) So intent was Ruggles on securing the house where he was then living, and an acre surrounding it, that he got Barrett to agree to a penal sum of $1000 should Barrett break the contract. The arrangement was for Ruggles to pay fifty dollars down and another $440 over five years and the property was his. These were good terms for the day. Dr. Barrett was perhaps supportive of the venture and had prior contact with the Community—he treated NAEI member Louisa Rosbrook a year-and-a-half earlier for lung complaints (DWS to JAS, July 26, 1844). Some historians have thought the “oil mill house” referred to the old oil mill itself which, during the time of the NAEI had been fitted out with bathing facilities for the members.

At the outset, it is doubtful whether Ruggles ever intended to become the respected hydropathic “Doctor” he did. He was still struggling with his own self-treatment. This passage from an article in the Liberator, December 21,1849 accurately sums up where he stood early in 1846.

Having carefully watched the effects of the water treatment upon his own person, and becoming familiar with the various applications of the liquid element, and possessing a sound judgment and rare intuition, he was led to turn his attention to this mode of curing diseases for the benefit of invalids in his immediate neighborhood, though not dreaming of ever placing himself at the head of an infirmary. As one case after another was successfully treated by him, he found his patients multiplying to such an extent as to render some kind of an establishment necessary; but as he was without pecuniary resources, he could do no better at first than to hire a small, inconvenient dwelling, with poor accommodations for half a dozen persons.

On August 4, 1846 the following brief article appeared in the Hampshire Gazette alongside an article promoting G. W. Benson and J. P. Williston’s Bensonville Manufacturing Company which had taken over the factory boarding house and converted it to cotton manufacture. Ruggles was now ready to forge ahead and grow his own new business.

Mr. David Ruggles has had a water-cure establishment in operation, on a limited scale, at Bensonville, in this town, for some months past. Encouraged by his success, he has made, and in part, completed, arrangements for the accommodation of a larger number of patients. Individuals in town have advanced $2000, which is secured in stock in the establishment. Mr. Ruggles has commenced the erection of a building, about 50 by 36 feet with an ell part which is calculated for the accommodation of 30 to 40 patients. It is to be completed, we understand, by about October. The supply of water is said to be abundant and good. It is stated that Mr. Ruggles has refused 50 applications to receive patients since the first of Jan. last. If this be true, he will find no difficulty in filling up his house when it is done.

By December the sanguine expectations reflected in the August article had dissipated and the stress of an undercapitalized start up are evident in this letter from Ruggles to Wendell Phillips on Dec 2, 1846 (Crawford Blagden Collection of the Papers of Wendell Philips, Houghton Library, Harvard University, 1068)

It is with feelings of reluctance that I trouble you with this, but I am compelled with necessity to do so. Since I am much disappointed by Mr. Sanger of New York, who was to have furnished two hundred dollars, but who has recently well nigh failed in business. If I get anything from him, it will not be until late in the Winter or Spring. I cannot therefore depend upon it at all, as I am to have all my business arrangements completed within the present month. As I need four hundred dollars instead of two hundred, to be safely in possession of my Establishment. I feel that I shall fail entirely unless you or some friends in Boston can afford me relief. I have now five patients, two of whom require daily attention of symptoms; it is therefore impossible for me to leave home, or I should go to Boston with Friend Benson, who I expect will be with you to-morrow or next day—when I trust that you will fall upon some successful plan to help me on to my feet.

Perhaps his solution to his problem, with his new building now complete, was to remortgage his property to Benjamin Barrett and to J.P. Williston which he did, raising $1600 on December 10, 1846. (Hampshire County Record Book 116, p. 81)

He got over the hump, and as the water cure expanded the hoped for 30 or 40 patients appear to have materialized during 1848. While William Lloyd Garrison stayed at the water cure between July 18 and October 20, 1848 the clientele varied between 18 and 23 (The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, vol. 3). The Courier and Herald reprinted a Springfield Republican article on September 26, 1848 that reported:

His establishment is capable of accommodating between thirty and forty patients, and it is at present full; indeed, he has been obliged for many weeks past, almost daily, to turn away applicants.

As a boarding house, a gymnasium, a wash house, indeed an entire campus came into being, and real estate holdings totaling nearly fifty acres accumulated, the “old Barrett house” remained a functioning part of the complex. It does not appear, however, to be where he was living when he died on December 16, 1849 from an inflammation of the bowels. His long struggle, to achieve the health he so desired for himself and others, was at an end.

Part 3 to come.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home